Alcuin Bramerton Twitter .. Alcuin Bramerton Medium

Alcuin Bramerton profile ..... Index of blog contents ..... Home .....#1ab

Picture: Jane Austen - intimate garden scene with chintz.

...........................................................................

In English Letters, only William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and Charles Dickens (1812-1870) can rival Jane Austen's continuing international appeal as a major author worthy of educated attention.

Writing between 1787 and 1817, Jane Austen did things with characterisation, with dialogue and with English sentences which had never been done before. She was, perhaps, the most surprising genius in all English Literature.

Her novels manifested a narrative sophistication and brilliance of dialogue which were unprecedented in English fiction. She introduced the free indirect style, filtering her plots through the consciousness of her characters, and she perfected fictional idiolect, fashioning habits of speaking for even minor characters which rendered them utterly singular.

Austen's brilliance was in the style rather than in the content of her writing. The potent success of her characterisation was a matter of formal daring as much as psychological insight. We hear her characters' ways of thinking because of Austen's tricks of dialogue; their peculiar views of the world are brought to life by her narrative skills.

...........................................................................

Picture: Anne Hathaway as Jane Austen reading by a window.

...........................................................................

Pub quiz questions tend to quaintness when they address Jane Austen novels. Are there any scenes in Austen where only men are present? Who is the only married woman in her novels who calls her husband by his Christian name? How old is the ridiculous Mr Collins?

In Jane Austen, the smallest of details - a word, a blush, a little conversational stumble - reveal people's schemes and desires. Austen developed writing techniques which rendered her characters' hidden motives audible, including motives which were hidden from the characters themselves, and furnished her readers with new opportunities to discern these motives from the slightest clues within dialogue and narrative.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) talked about Jane Austen's "exquisite touch". This was an appreciation of her precision. Accuracy was Austen's particular genius. In noticing minutiae the reader was led to the wonderful connectedness of her novels, where a small detail of wording or motivation in one place would flare bright with the recollection of something, now significant, which had happened much earlier. Every quirk noticed led the reader to a subtle design.

Jane Austen taught later novelists to filter narration through the minds of their own characters. It was Austen who first made dialogue the evidence of motives which were never stated explicitly. It was Austen who first made the morality with which her characters acted depend upon the judgement of her readers.

In 1901, a confused Joseph Conrad wrote a letter to H.G.Wells. "What is all this about Jane Austen?" he asked. "What is there in her? What is it all about?"

What matters in Jane Austen? is written by Professor John Mullan of the English Department at University College London (UK). It is published by Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408820117.

...........................................................................

Picture: Row of pink Jane Austen volumes.

...........................................................................

The casual EngLit mind inclines to the view that the Gothic enthusiasm in English novels first became visible in 1764 with the publication of The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole. This was eleven years before the birth of Jane Austen in 1775. Did the new Gothic novel genre influence Jane Austen's writing? Hilary Mantel says it certainly did. While Jane was still a teenager, she parodied the Gothic mercilessly in her early writing.

In the summer of 2017, when a big JaneFest was being cranked up to commemorate the bicentenary of the writer's death in 1817, The Guardian newspaper (London) invited seven sober literary types to comment on Jane Austen's work. Three of these were Hilary Mantel, Claire Tomalin and Ian McEwan.

Hilary Mantel observes that "Charlotte Brontë did not like Jane Austen because she thought she was mimsy, with a fenced-in imagination. But the teenage Jane was ruthless, well read, exuberant and scathing. She understood the cult of sensibility, and sniggered at it."

"Austen parodied the Gothic, long before she wrote Northanger Abbey: horrid secrets, fulminating infatuations, astonishing coincidences, catastrophic lapses of memory, road traffic accidents and the theft of £50 notes."

"Every 'coroneted carriage' contains a long-lost relation. Orphaned babies - perfectly able to relate their sensational histories - are discovered in haystacks. In Henry and Eliza, two hungry children bite off their mother’s fingers."

"If there is no logical connection between the actions of Austen's early characters, it’s not because she’s child-like; it’s because she’s clever. She has understood that in genre fiction the conventions of the form overrule reason: so whenever the plot defeats itself, or the author loses interest, 'Ah! what could we do but what we did! We sighed and fainted on the sofa.' ”

"That is from Love and Freindship (sic), one of the longer stories. Some of Austen's early writings are only a few lines long. But Jane’s shorthand is savage. No cliché goes unmolested. If her mature novels elicit a knowing smile, the juvenilia makes you laugh out loud. These squibs, remnants and broken stories, incised with glee between the ages of about 11 and 17, show how deep her art goes into her early life, and how aware she already is of the techniques and tropes that will later produce her popularity."

...........................................................................

Picture: Pride and Prejudice. Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy.

...........................................................................

Claire Tomalin notes that Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice was said to be 'too clever to be by a woman' by a not very clever admirer when it was published in 1813.

"First drafted in the 1790s, the manuscript had to be carried about carefully as the Austen family moved from place to place. Austen herself called it 'my own darling Child', and enjoyed reading it aloud to friends and family, but she published it anonymously, since ladies did not promote themselves."

"The narrative is brilliantly confident from its famous Johnsonian start, 'It is a truth universally acknowledged .…' From then on it is all drama, largely told through the voices of its characters, and mercilessly funny in presenting fools: Mr Collins, the first of Austen’s unctuous clergymen, and Mrs Bennet, the mother from hell."

"Mrs Bennet’s least favourite daughter, Elizabeth, stands alongside Shakespeare’s Rosalind as one of the most interesting heroines ever written, and surpasses her by being more complex, multi-stranded and capable of dark thoughts."

"Elizabeth Bennet tells her sister: 'You are a great deal too apt to like people in general,' and, 'The more I see of the world, the more I am dissatisfied with it.' ”

"Growing up with mismatched parents has sharpened her take on life and she looks at the world closely and critically - like a writer, you might say. She is not Austen, but she is what Austen thought a young woman should be: tough, energetic, observant, forthright."

"Elizabeth is set to enjoy her youth and freedom - dancing, friendship, the prospect of love and marriage - but Austen does not hesitate to give us the brutal truth about economics for women of her time by showing her best friend Charlotte ready to marry a man she neither loves nor respects because it is better than becoming a despised old maid. Charlotte regards selling her body and domestic skills for married status as normal. Elizabeth is dismayed but has to accept that her friend has little choice."

"Pride and Prejudice is structured to give Elizabeth temptations, dramatic reversals, discoveries and arguments in her own love affairs."

"At the climax of the book she is attacked by the aristocratic aunt of her lover, and in a virtuoso chapter the two women play out their battle, a verbal game of tennis with Lady Catherine de Bourgh confident of defeating a social inferior."

"Instead Elizabeth coolly wins every point. Although she says “I am a gentleman’s daughter”, this is not how she triumphs over Lady Catherine - it is by insisting on her right to act “in that manner which will, in my opinion, constitute my happiness”. This is her own declaration of independence."

...........................................................................

Picture: Northanger Abbey. Jane Austen. The ladies and gentlemen in Bath.

...........................................................................

Ian McEwan quotes a passage from Northanger Abbey:

'Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English, that we are Christians. Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you. Does our education prepare us for such atrocities? Do our laws connive at them? Could they be perpetrated without being known, in a country like this, where social and literary intercourse is on such a footing, where every man is surrounded by a neighbourhood of voluntary spies, and where roads and newspapers lay everything open? Dearest Miss Morland, what ideas have you been admitting?'

'They had reached the end of the gallery, and with tears of shame she ran off to her own room.'

McEwan first read this passage in 1965, at the age of 17. It made a great impression on him. The heroine’s unruly imagination is suddenly tethered by this vigorous remonstration from General Tilney.

"What’s striking is that in the very early 19th century, before the railways had transformed the country, and long before the telegraph, the General evokes a society that is intricately connected, where no one can hide from public scrutiny when a network of communications and media can 'lay everything open.' ”

"No place here for wild and foolish imaginings. Perhaps this is the very essence of the condition of modernity - always to believe one has arrived in one’s time at the summit of the modern."

McEwan says that Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey profoundly influenced his own novel Atonement. Indeed, General Tilney’s resounding words form the epigraph chosen for that book.

The Guardian's seven pieces on Jane Austen can be found here.

...........................................................................

Picture: Polite book circle. What matters in Jane Austen?

...........................................................................

These days, in polite book circles, it is not unusual to encounter the enquiry: Was Jane Austen a feminist writer? There are opposing views on this. The Scottish Book Trust offers two.

Brianne Moore says no. "Was Jane Austen a feminist? Personally, I don’t think so. I highly doubt she’d have considered herself a feminist, even if you travelled back in time and explained to her what feminism was. Jane did, after all, live a very conventional life, following the rules that a woman of her time and position was supposed to follow, to the letter."

"She did create some very spirited and strong female characters who many argue made their own decisions in life, rather than adhering simply to what society expected of them - after all, didn’t Lizzy Bennet turn down Mr Collins? But the thing is, those characters inevitably wound up fitting into exactly the mould their patriarchal society expected them to: they all married wealthy men of position, and took their places as good wives."

"Women in Austen’s stories who are particularly outspoken or don’t behave in the way proper young ladies are meant to (polite and decorous; not too flirtatious; not too wildly imaginative) are frequently punished: overly emotional Marianne Dashwood gets her heart broken; Lydia Bennet winds up married to a rogue, and the list goes on."

"Those ladies who realise the folly of their ways and fall in line, however, reap their reward. Marianne becomes more sensible (less prone to wandering about the countryside and more likely to sit quietly indoors) and marries the upright Brandon; Catherine Morland gets her imagination under control and marries Henry Tilney; Emma leaves off matchmaking, controls her tongue and lands Knightley."

"In Austen, whether or not you get your wedding in the end (the expected, conventional ending for a young woman) is highly based on how well behaved you are in the eyes of a highly patriarchal society, which doesn’t read as terribly feminist to me."

...........................................................................

Picture: Jane Austen. Engraving of the only known portrait.

...........................................................................

Leila Cruickshank, however, says yes, Jane Austen can be viewed as a feminist writer. "There are many potentially anti-feminist messages in Jane Austen, including the requirement for women to marry, the depiction of some women as highly silly, and the fact that the men sometimes save the day. Yet to read Austen as anti-feminist is to lose sight of the purpose of feminism."

"Feminism gets bogged down today in debates about bra-wearing, misandry or ‘sisterhood’, but the key message of feminism is simple: equality between the sexes."

"Austen lived in a time when the very notion that women could hold rational opinions and manage their own affairs was highly controversial, and while Austen is certainly not a radical in the sense that Mary Wollstonecraft is, she repeatedly demonstrates that women who are slaves to emotion or who follow the dictates of social expectations over their own intelligence, cannot thrive."

"Mansfield Park’s Fanny is accused of ingratitude for refusing to marry her guardian’s son, yet her decision is shown to be correct, and her guardian eventually recognises her superior judgement."

"Austen promotes the idea that women’s decisions and choices are equally important to men’s. Both Mr Collins’ and Mr Darcy’s proposals to Elizabeth fail due to their misunderstanding of her feelings of self-respect. Elizabeth could not respect herself if she married Mr Collins (indeed, although she is able to understand Charlotte’s decision, she is unable to respect it and finds the marriage comical and, frankly, embarrassing)."

"Likewise, her sense of herself, her views of her family, is strong enough to refuse a socially-enticing marriage with Darcy, while Darcy is stunned to be turned down. This sense that a woman’s right to self-determination is more important than the desires of a man, is right up there with feminist mores."

"Austen herself was well-read and educated for a woman, and her novels repeatedly comment on the inherent weaknesses in women’s education and the need for them to be well-read."

"Her interest in how women should support themselves is also clear - she sees marriage as the only option for a non-financially independent woman, it is true, but this was very much a practical consideration of the time. Emma states that there is no need for her to marry, because she is financially stable."

"Austen does wholeheartedly believe that men and women should be companions to each other as well as spouses - consider her depiction of Mr and Mrs Bennet. The fact that she wants women to make choices based on love as well as financial reasons asserts both their ability to make rational choices, and their right to pursue happiness. And that was pretty feminist for the time."

The Scottish Book Trust is here.

In recent years some have noticed that Western feminism has fractured painfully and broken in pieces. This happened after common-sense thinking fell out of fashion. These days most hardcore feminists don't give a whore's wank about Jane Austen. Her writing isn't about the working class and it is not about blacks.

In an open information era where content is queen, it appears that many among the feminist Sisterhood are more concerned about the colour of the packaging than about what stirs inside. Perhaps they should marry Mr Collins.

...........................................................................

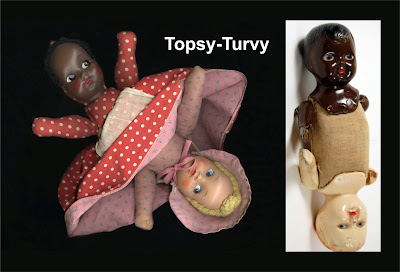

Picture: Topsy-Turvy upside down black and white doll.

Picture: Floating woman reading book.

...........................................................................

...........................................................................

The Republic of Pemberley

And a pair of ears listened

A new book offers advice to its reader

The libraries do not fool us

Entire human knowledge - FAQs

Living text entity

Demanding lover

Novel in Burnley

Reasonable request

Small visitors

............................................................................................................................................

Picture: Mary Wollstonecraft's radical move in the 1790s.

.%20%231ab.jpg?SSImageQuality=Full)

............................................................................................................................................

Index of blog contents

No comments:

Post a Comment